Long Read

Tomorrow’s Earth: 2055

Newtok, Alaska

It is 2055 and the village of Newtok on the coast of the Bering Sea in Alaska is no more. The inhabitants moved to Mertarvik on nearby Nelson Island, some three decades ago. The remains of old houses, stores and outbuildings, the modest infrastructure of a Yu’pik community, have mostly disappeared into the sea as relentless waves and spring tides have deeply eroded the shoreline.

Several other seaside villages have experienced the same fate. It was not always like this. In the late 20th Century, Newtok was one of several thriving Alaskan neighbourhoods living off a mix of sealing, fishing and State handouts. The change came in the early noughties. The all-dominant feature of life in this part of the Arctic, the sea ice, began its precipitous reduction[1]. The winter ice started forming much later in the year, allowing early winter storms to wreak havoc on the boulder-strewn coastal plain, eating back the coastline[2].

In similar fashion the ice that did form melted away and was rotten much sooner in the Spring. Travel to fish or hunt seal was limited. The long days of summer became much warmer, youngsters played bare-chested as never before and it was even possible to grow vegetables. It rained, a phenomenon that rarely if ever occurred in previous generations. Worse, the rapid melting of the frozen ground created a quagmire of pits, holes and runnels of mud and stones[3]. As the melting accelerated many buildings were undermined making them uninhabitable.

The Yu’pik world was topsy-turvy. It was clear the game was up. Newtok was no longer habitable. The small society built up over many years was destroyed by climate change and soon it was gone[4]. Andrew John, Newtok tribal administrator commented in 2019, “I think as a people, our greatest attribute has been our ability to adapt,” John says. “Our people have been flexible. We’ve found a way.”[5]

Mass Migration: escaping north

To the South in Alaska a different phenomenon is unfolding. The once marginal land along the coast fringing the Pacific Ocean is receiving thousands of immigrants as the climate ameliorates and conditions improve for habitation, farming[6] and new industries. Fresh communities are springing up and flourishing but placing pressure on existing State infrastructures that can barely cope. Social tensions are rising rapidly as long-standing Alaskans, whose families value their isolation and rugged independence, are being marginalised by younger cohorts of newcomers with very different community cultures.

The State has intervened using its own funds and Federal support to assist the assimilation. Many of the incoming individuals and families have moved steadily, some say precipitously, from States worst hit by impacts of changing climate, in the south of the USA—California, Texas, New Mexico and Arizona. Here there is nothing but stories of tragedy and loss. As the unremitting heat has built up, citizens have been subject to agricultural failure, water shortages and catastrophic wildfires on an unprecedented scale. Conditions across the region are akin to the great Dust Bowl in the southern Great Plains of the 1930s.

The causes, however, are far removed from the agricultural malpractice of the early 20th Century, although the ultimate cause, the excess burning of carbon, is similarly a consequence of human industrial activity. Great tracts of these States have become uninhabitable and in desperation one of the greatest migrations within the USA has sent people north to States stretching from Washington to Michigan. Many have chosen to settle in Alaska as administrations in some Capitols have applied the brakes on new settlements. This account does not have space to describe the parallel and unprecedented movement of citizens from the now flooded coastal tracts of the Atlantic States from Florida to New England[7]. Their desperation has added immense pressure to Federal as well as State resources.

Whereas in the nineteenth Century the great movement of people was West in search of new opportunities now in the mid 21st Century people are heading North, quickly and in despair. Canada has already started regulating its borders in an unprecedented move to reduce the inflow of US Citizens who over the past ten years have moved in large numbers beyond the 49th parallel. Difficult to patrol and police, the border is now the scene of skirmishes and lawlessness which has swung the balance in favour of Alaska.

These pressures within the USA are the tip of the iceberg compared with the assault on the boundary with Mexico. Forty years ago, the harbingers of mass migration from South and Central America were just beginning to be experienced. Now the border is a military no mans’ land patrolled by thousands of heavily armed troops. The death toll along the boundary is legion but official statistics are classified. Large tracts of Mexico and elsewhere have been turned into an agricultural wasteland[8].

In other areas of the world, states, regions and individuals are confronting similar acute environmental and societal challenges.

Mass Migration: islands and Asia

With sea level rising now, in 2055, by 5mm each year and a total of half a metre since the beginning of the Century, shoreline lowlands are becoming rapidly uninhabitable. The latest estimates by the United Nations are that a third of a billion people have lost their homes and businesses and a further half billion are highly vulnerable with the prospect of their displacement by 2100.

Small low-lying island nations have been some of the first to be compromised. Whilst their populations are typically tiny, their circumstances are totemic. The Maldives, the Marshall Islands, Tokelau and Tuvalu, and Kiribati possess few areas which are not submerged by storm surges. In 2000, 80% of the Maldives was determined to be lying below one metre above sea level. Half of that has now disappeared underwater. Most of the lowest islands have been evacuated despite a raft of costly adaptation measures such as sea walls and wetland zones[9].

In desperation, the government in the Maldives has sought to re-locate its population—a force majeure which threatens its very statehood under the Montevideo Convention[10]. This was first mooted in 2008 under President Mohamed Nasheed: “We can do nothing to stop climate change on our own and so we have to buy land elsewhere. It’s an insurance policy for the worst possible outcome.”[11] India, Sri-Lanka and Australia were seen as possible destinations. Despite an attempt to remain, the nation has succumbed to the inexorable power of rising seas and moved its much smaller population, already diminished by voluntary emigration. India and Australia shut their borders. An enclave in Sri Lanka was agreed following several years of intense and difficult negotiations with Colombo. There were inevitable concerns and clashes with local people whose lands were appropriated. More will come as the situation continues to worsen and more people are displaced from other adjacent island groups.

Elsewhere in the Indian Ocean, similar problems are being experienced at an entirely different scale in the delta regions of the rivers Ganges, Brahmaputra, Irrawaddy (Ayeyarwady) and further east, the Mekong, and in China, the Pearl. These already low-lying and swampy tracts that supported several hundreds of millions of people at the beginning of the Century have experienced widespread flooding. Villages, towns and cities have been wiped out and the agricultural base of these densely populated communities destroyed, creating food crises.

The extensive intrusion of saltwater has compounded the difficulties, rendering the effected land useless for crops and contaminating drinking water supplies. Industry and businesses erected on cheap wetlands in the past have been lost, making uninsured and unprotected artisans destitute. In these already highly populated countries, the movement inland of people away from the Deltas has increased the pressure on habitable living space. Ethnic confrontations have been widespread and instability and uncertainty are rife. National governments have used the military to control the worst outbreaks of violence as citizens seek refuge. The death toll from drowning, starvation, disease and bloodshed has been immense.

Some Science

This short hypothetical, highly selective exploration of possible future outcomes of on-going, accelerating and increasingly severe global climate change is based on recent scientific analyses by international and regional bodies, which are widely available[12].

The IPCC analysis should be taken as the most reliable, based on consensus views of large numbers of able scientists. While our scientific understanding of climate change processes constitutes a reasonable first order approximation, we are still refining estimates continuously, incorporating new data, research findings and the unforeseen.

Projections (rather than predictions) are lagging behind what we are experiencing directly as new observations are added. The speed of change is becoming noticeably faster. Impacts are scaling at high frequency and becoming more severe. The extremes are lasting longer. Repeatedly we experience the unexpected.

This is why chasing specific targets is deeply uncertain. Basing policy on them is at best difficult and at worst dubious as they are transitory under different circumstances. Policy makers tend to be conservative, politics is a crude and partial filter of scientific advice and the public does not like change. These factors slow our ability to embrace the latest information and prognoses. We are frozen in the headlights of climate change.

This is compounded by the fact that many forecasts or projections are couched in probabilistic language. The IPCC, for example, referring to “Global Warming of 1.5oC” uses “confidence” limits such as “low”, “medium” and “high”. This is understandable given the need for consensus, to defend the process of data acquisition and modelling and to be readily comprehended.

What tends to be omitted are worst case scenarios. These are frequently difficult to endorse and can have political consequences of some magnitude. Yet in the past several decades the environment from global to local scales has been subject to events and circumstances lying at the outer boundaries of probability. These situations are noted but rarely applied explicitly.

Some examples may illustrate this better. For several decades in the 20th Century flood predictions, heatwave forecasts and similar extreme weather conditions were often explained in terms of magnitude-frequency analyses. Flood magnitudes were designated on scales of 10-year, 100-year or even 1000-year events. Engineers and civil authorities used these with confidence for the planning and construction of a wide range of infrastructure and emergency response.

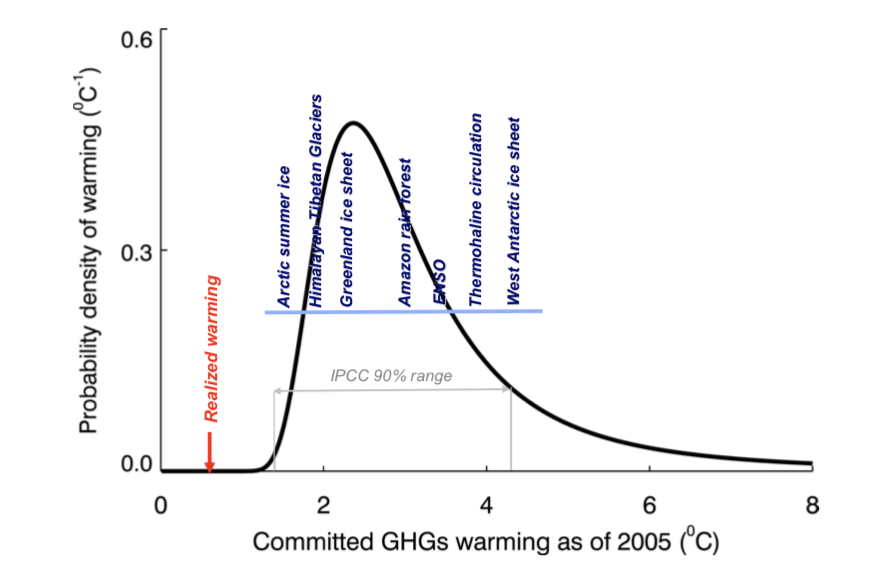

Most of these normative models have been rendered useless by progressive climate change. The simple sticking-plaster method of coping with the changes has been to re-designate recurrence frequencies. The 100-year flood becomes the 20-year flood. There remains uncertainty in the statistical basis for such re-designations for which the numbers of ‘new’ occurrences may be insufficient to be analytically robust. It is generally assumed that events follow a normal distribution against temperature rise. Numerous studies over the last decade have highlighted the range of probabilities attributed to extreme events. One such is shown below – an illustration from Ramanathan and Feng[13]:

Probability distribution of committed warming (1750-2005) from Ramanathan and Feng. In this study peak probability is at 2.4oC. Also shown are “climate tipping elements” against respective temperature thresholds.

[GHG – greenhouse gasses; ENSO – El Nino /Southern Oscillation]

The emergence of ‘tipping-points’ is a further disruptive element, whereby natural systems experience progressively changing input conditions that generate different, ‘dangerous’ and less predictable conditions.

In recent years there has been increasing concern that many of the world’s bio-physical systems may be approaching such thresholds as global temperatures rise steadily. One such is the seasonal formation of sea ice in the Arctic Ocean in which the increasing heat gain from open water provides a positive feedback culminating in an ice-free Arctic. Biological systems exemplified by coral reef and tropical rain forest ecosystems are also compromised by positive feedbacks. An added complication at global level is that ecosystems are most likely subject to different temperature thresholds. Lenton and colleagues have discussed these tipping points in more detail and have indicated the likelihood that some systems may concatenate, creating a temperature-induced cascade effect with significant, if not potentially disastrous, world-wide impacts.[14] [15]

In this exercise I have taken a sceptical opinion of the conservative view of climate change predictions as these appear to lag behind and underestimate what we have experienced on a world-wide basis to date.

As a recent Nature article by Kulp and Strauss concludes: “…coastal communities worldwide must prepare themselves for much more difficult futures than may be currently anticipated.”[16]

Despite these unmistakable signals COP-25 in Madrid in December 2019 has continued the international wrangle over carbon reduction commitments and financial support for poor and vulnerable countries—over how much, when and how. Movement is glacial.

David J Drewry[17]

January 2020

Footnotes

- “Arctic Sea Ice News and Analysis”, National Snow and Ice Data Center, Boulder Co.(nsdic.org) ↑

- “National Assessment of Shoreline Change: Historical Shoreline Change Along the North Coast of Alaska, U.S.-Canadian Border to Icy Cape,” USGS Open-File Report 2015-1048 ↑

- Permafrost in the Arctic has become up to 2°C warmer and has vanished in several places in the southern part of the Arctic. The southern border for permafrost has thus retreated 30-80 km northward in Russia between 1970 and 2005 and 130 km in Quebec over the past 50 years (AMAP, 2017. Snow, Water, Ice and Permafrost in the Arctic (SWIPA) 2017. Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP), Oslo, Norway. xiv + 269 pp) ↑

- NPR “Residents Of An Eroded Alaskan Village Are Pioneering A New One, In Phases” November 2, 2019 ↑

- Craig Welch “Climate change has finally caught up to this Alaska village” National Geographic, 25 October 2019 ↑

- 50% increase in length of growing season (G.Juday (University of Alaska)) cited in U.S. Global Change Research Program, 2009 ↑

- States at Risk Report Card (2018) for Florida put 4.5M people at risk of 100-year coastal flooding ↑

- 40% to 70% decline in Mexico’s current cropland suitability by 2030 and 80% to 100% decline by 2100 (Climate: observations, projections and impacts: Mexico, UK Met Office 2011) ↑

- World Bank February 2018 “Maldives’ Wetlands help fight climate change” ↑

- Four criteria are necessary for Statehood under this Convention: a clearly defined territory, a permanent population, a government and the capacity to enter into relations with other states. ↑

- Randeep Ramesh “Paradise almost lost: Maldives seek to buy a new homeland”, The Guardian 10 Nov 2008 ↑

- Stocker, T. et al. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, New York, 2013).US Global Change Program, Climate Science Special Report (nca2018.globalchange.gov); Stern, N 2017 The Economics of Climate Change, CUP692pp; ACIA, 2005. Arctic Climate Impact Assessment. ACIA Overview report. CUP. 1020 pp. ↑

- Ramanathan, V and Feng, Y 2013 On avoiding dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system: Formidable challenges ahead. Proceedings National Academy of Science, Vol. 105 (38), -14245-50 ↑

- Timothy M. Lenton, Hermann Held, Elmar Kriegler, Jim W. Hall, Wolfgang Lucht, Stefan Rahmstorf, and Hans Joachim Schellnhuber: Tipping elements in the Earth’s climate system. PNAS February 12, 2008 105 (6) 1786-1793; first published February 7, 2008 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0705414105 ↑

- Lenton et al. Climate tipping points — too risky to bet against. The growing threat of abrupt and irreversible climate changes must compel political and economic action on emissions. Nature 575, 592-595 (2019) ↑

- Kulp, S.A. and Strauss, B.J. 2019 New elevation data triple estimates of global vulnerability to sea-level. Nature Communications 10, No. 48449 ↑

- Professor David Drewry is Non-Executive Director for the Natural Sciences at the UK Commission for UNESCO and Honorary Fellow at Emmanuel College, Cambridge University. The views contained in this article are personal to the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the UK National Commission for UNESCO ↑

Contact Us

We welcome comments on all aspects of our editorial content and coverage. If you have any questions about our service, or want to know more, please e-mail us or complete our enquiry form:

Submit an Enquiry